This is the first biographical write-up within the Family Stories series. The character of Lee Yew Beng (LYB) is documented here, based on various sources of stories. As the primary author of this article, I am just one of his 38 great-grandsons.

Version History

- Originally published: 17 January 2015

- Update #1: 31 January 2015 (Kuching sourced updates)

- Update #2: 8 April 2016 (Minor correction to dates & small edit for Lee Swee Hock)

- Update #3: 20 August 2016 (Addition of link to photo restoration)

- Update #4: 22 August 2016 (Updates based on recent trip to Kuching)

- Update #5: 23 August 2016 (Integration of minor details extracted from 2004 Family Tree)

- Update #6: 1 March 2022 (Replacement of photo to larger version; minor updates)

Name & Identity

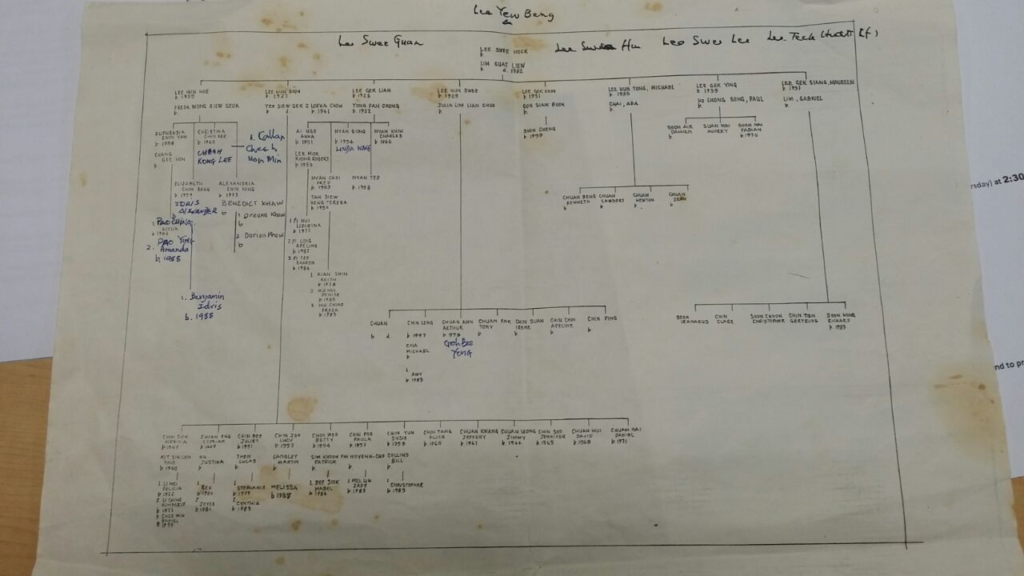

An invaluable family tree mapping was emailed to me, which reveals the true name of my great-grandfather, who up until now had been recorded (as per the tombstone in Penang as LEE Cha Boh) is actually LEE Yew Beng!

This vital piece of information has been accepted without too much scrutiny because it was written in the handwriting of the eldest grandson and given his career as a high court judge, we all can accept his credentials and authority on the matter.

For various reasons, it was agreed to mark the tombstone not as Lee Yew Beng, but instead “LEE Cha Boh”. In Chinese, Cha Boh translates to English as “girl”. Even the Chinese characters on the tombstone reflect the intentional use and referral to the individual as “Lee Cha Boh”.

The generalised reasoning to explain this is that this change in identity was to help conceal the individual, both in life and in death from past spirits of even family. It is therefore possible that adopting the name “Lee Cha Boh” was part of the emigration process from China. Understanding the historical context of these time periods and the emigration patterns of typical Chinese coming to Malaya was that some would return eventually to China, bringing back their new-found wealth to their family waiting in China, or else start over with a new family. Lee Yew Beng is thus an example of the latter lifestyle and also where he still honoured his parents’ arranged marriage.

Given the new information provided in January 2015, it is possible that Yew Beng feared the curse that his mother had originally threatened, and the use of Lee Cha Boh was adopted thereafter to ward off and confuse any spirits. Whether he used the moniker “Cha Boh” throughout his life in Penang, or only as part of the funeral/tombstone – it is extremely hard to know. What we do know is that the younger generations (particular grandchildren/great-grandchildren) of the family in Penang had always referred to their ancestor as Lee Cha Boh.

The family today remains indebted to the preservation of our ancestor’s true identity and name by his grandson Lee Hun Hoe.

Family Tree Position & Generational Analysis

UPDATED 31/01/2015: As part of this document, I have managed to update one son’s entire branch to include up to 77 new individuals.

Lee Yew Beng forms the top-most branch of my family tree holding the title of the earliest known ancestor of mine, estimated to have lived an approximate lifespan of some 56 years across the late 19th century and early 20th century. According to the Family tree descendent report, Yew Beng’s blood flows through 206 individuals as of March 2022:

- 1st generation (1900 – 1920) [5]

- 4 sons

- 1 daughter

- 2nd generation (1929 – 1955) [32]

- 13 grandsons

- 19 granddaughters

- 3rd generation (1952 – 1987) [70]

- 36 great-grandsons

- 34 great-granddaughters

- 4th generation (1974 – current) [69]

- 27 great-great-grandsons

- 42 great-great-granddaughters

- 5th generation (2003 – current) [31]

- 17 great-great-great-grandsons

- 14 great-great-great-granddaughters

A quick commentary to explain the dates and generations: the date range is based on birth years of each generation, so the first generation of children of Yew Beng were all born within the 20-year range. Given this range, the next generation born to form the grandchildren generation has an even greater range of birthdates from 1929 right up to 1955, when the youngest members of that generation were born.

It thus reflects the cycle of life in those days that an individual would realistically live to see the start of their second generation, whereas today, with the vast majority of the grandchildren still alive today, they all themselves enjoy being grandparents and potentially even great-grandparents. In this way, the extended longevity of modern society is reflected in the family tree of Lee Beng.

The other key observation of this profiling of the family tree is that the generations originally were distinct and separate, whereas the latest 4th and 5th generations have an incredible overlapping span of dates. The previous separation of dates distinguishing generations is only observable between the 1987 end of the 3rd generation and 2003 starting point for the 5th generation. Whilst members of the 3rd generation have a 38 maximum age difference, any new births to the 4th generation will be up to 40 years apart, or 1-2 generations apart within the one genealogical generation.

Chinese Heritage

The story of Lee Yew Beng, particularly his Chinese origins and which province/city he came from remain quite obscure other than a suspected year of birth around 1875 and the Fujian province. Family discussions held in Kuching, 2017 even speculate and suggest 1875 was the date/year of disembarkation in Malaya, but how old Yew Beng/Cha Boh was remains an elusive mystery.

When we delve deeper into historical contexts to understand this better – we believe Lee Yew Beng left China on his own. He may have been an only child since there is never any mention of siblings. It is however possible that he was merely the eldest (?) of a family back in China where the younger siblings were not of age. It is also more likely that Lee Yew Beng had a certain level of maturity and capability – he would not have made that voyage – something more risky and dangerous in those days – unless he were at least 15-16 years old.

New information (stories) available from the youngest grand-daughter via the Swee Hock branch of the family has now been acquired such that Yew Beng ventured to Penang/George Town in Malaya on his own, but betrothed to a girl back in China. This girl was staying with Yew Beng’s mother whilst Yew Beng pursued a new life in George Town.

Given this information, it also helps us estimate

Alternative #1

It is assumed that, having arrived at the main port of George Town, Lee Yew Beng decided to seek employment in the Kedah state capital of Alor Star where he took up the trade of tin mining. In those days, the Clan jetties would have been active in receiving and assisting Chinese migrants such as the young Yew Beng. The Lee jetty, as one of the bigger clans/ societies would have helped provide accommodation and contacts leading Yew Beng to pursue work further north in Kedah. The Clan house may have also been instrumental in matchmaking Yew Beng to local woman Chan Saw Kooi. In pursuing a life in Kedah, it is quite possible that the adults were witness to the 90-day wedding festival of the sons of the Sultan of Kedah, which transpired over the period of June to September 1904. Lee Yew Beng worked in the tin mines of Kedah and lived in Alor Star where he met his wife Chan Saw Kooi.

Alternative #2

In the first write-up for Lee Yew Beng/Cha Boh, the thinking back then suggested that he journeyed overland instead of via boat and that the trip took him through Vietnam and Thailand. If this was true, then the likelihood of Lee Yew Beng passing through Penang and the Lee Jetty/Lee Kongsi decreases. This account, written in the early 2000s also suggested that Lee Yew Beng found employment as a quarry master because this was his previous community expertise back in Fujian.

In both stories, the fact that Lee Yew Beng met Chan Saw Kooi in Alor Star, not Penang remains a constant undisputed fact.

Two Families

Chan Saw Kooi gave birth to four children, starting with three sons – Swee Guan (1899?), Swee Hin in 1906 (Year of the Horse), shortly followed by Swee Lee (1908, Year of the Sheep) and later in about 1919, to a daughter – Suan Gaik. When Yew Beng’s mother heard that her son had married and had a son (Swee Guan), she was not happy and brought herself along with the betrothed girl to Penang. At the wharf (?Lee Jetty – speculated?) Lee Yew Beng initially refused to proceed with the arranged marriage at which, his mother threatened to curse him for refusing to take the girl in. At this, Yew Beng immediately had a change of heart and accepted his betrothed. One son, Swee Hock was born to this union and with a birth year of 1901 (sourced from August 2016 trip to Kuching) fitting in between 1899 and 1906.

Swee Hock became considered the second son and by the time the daughter was born, the family had relocated to Penang. Whilst Swee Hin and Swee Lee were relative close in age – barely more than a year between them, Lee Yew Beng did not succeed in providing his sons with a strong sense of family duty and both sons grew apart. Further, whilst relations between the two youngest sons and Swee Guan were cordial, tension with Swee Hock was an apparent characteristic that left a tarnish on the family (see below).

Information recorded in the early 2000s suggested that the two eldest sons Swee Guan and Swee Hock were Chinese educated whereas the two younger songs Swee Hin and Swee Lee adopted a more Peranakan lifestyle and education in following the Western/English education system.

What little detail available of Lee Yew Beng and his life in then-Malaya is reflected in the outcomes.

Demise

On Saturday 28 March 1931, Lee Yew Beng died at the age of 56, but not before his sons Swee Hock & Swee Hin had fathered his first five grandchildren with another four more on the way. The story of Lee Yew Beng’s death is tied to the tin mine he was responsible for managing. It was said that his wife, Chan Saw Kooi, had taken the company’s payroll money out of the safe to fuel her gambling addiction. When Yew Beng discovered the safe empty and was unable to pay all the 300+ (number first recorded in early 2000s write-up) tin mine workers he commit suicide. Committing suicide in this manner was the most honourable action according to Chinese customs, which the Japanese seppuku concept derives from.

One of the curious realities besides the name change which is documented above is evident in the tombstone which remains unchanged from the original inscription whereby the eldest grandson of each son unfortunately leaves out Swee Hock’s first-born. Why this is the case, and whether it was in any way influenced by Chan Saw Kooi who would also join her husband in the tombstone, we can only speculate. Another inconsistency of the tombstone is the inclusion of an additional daughter in “Ah Mooi”. My father’s own recollection was that Ah Mooi was in fact a servant girl in the household of Lee Swee Lee. My father himself is immortalised in the tombstone since he was born the eldest grandson in his father’s household.

Given this information it suggests the tombstone inscriptions may have been primarily a responsibility shared between the two sons who lived in Penang. It is pure conjecture on my part, but given the strained relationships between brothers that these tensions influenced the decision making and future generations see the results immortalised in the tombstone.

Over the years, the present day grandchildren & great-grandchildren (my generation) have rebuilt family unity such that if we could, we would surely restore and correct the missing and misleading information currently enshrined. However, there are also sensitivities and customs of the past and Chinese heritage which may prevent this.

2016 August – Photo Restoration

View the details here, along with downloadable photo images.

Ongoing Legacy/Research

As documented in the Family Tree & Generational Analysis section, the legacy of Lee Yew Beng has reached far and wide. As the first known emigrant, his descendants continue to migrate according to the opportunities that the twentieth century fostered. No one alive today (as of 2015) was alive and present during the lifetime of Yew Beng. Those that are alive today who are old enough were not in close physical proximity to him, or had they been, would have been too young to remember,

All remaining knowledge of him is at best second-hand in nature; fragments of information learned by his grandchildren collectively. For decades, the best remaining evidence has been the tombstone which remains a rallying landmark in the Penang Mount Erskine Chinese Cemetery for all descendants to visit. Having said this, no story remains static for too long in this day and age, given the will and resources available to us in the twenty-first century. The following options remain open to myself and other interested family members who wish to collaborate on this genealogical study:

- Verification of information (names, dates & events) against official records, newspaper obituaries, etc…

- Malaysia (Penang/Kedah)

- China (Fujian)

- Verification/alignment of information to societies such as:

- Lee Kongsi (Penang)

- Mount Erskine Chinese Cemetery

5 comments

Comments are closed.