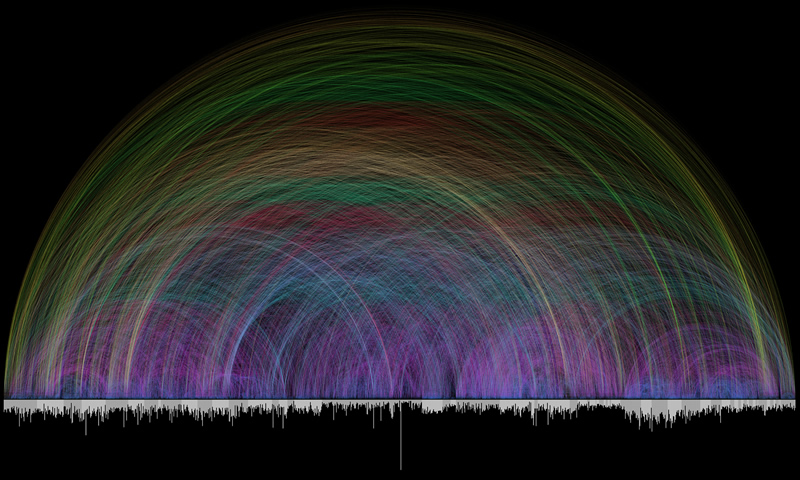

Understanding and appreciating the history of the bible requires us to consider it in parts. This article is thus by attempt at drawing together various sources of material to help focus on the origins and authorship of the 66 books of the Bible. The focus here is also on language and translations. The above diagram is sourced from Chris Harrison – BibleViz, and this link provides a detailed explanation behind the cross references.

Original Texts

Old Testament (39 books)

The Old Testament covers multiple historical periods of the Israelites/Jews, and can be further broken down as follows:

The Torah (Teaching): First 5 Books

- Genesis

- Exodus

- Leviticus

- Numbers

- Deuteronomy

These books are traditionally believed to have been written by Moses, with the exception of the last verses which document his death – believed to have been written by Joshua. The final form that we know the Torah today was achieved by 332 BC, with its authoritative status overseen by the intellectual elite who returned to Jerusalem after the Babylonian Exile. Even before this finalisation, by the 5th century BC, the Jewish understanding was such that the Torah was authoritative as the Law and Teachings.

Nevi’im (Former Prophets): 12 Books

Note – whilst we document 12 books in this section, if you combine 1 Samuel with 2 Samuel, 1 Kings with 2 Kings, and 1 Chronicles with 2 Chronicles, the number becomes 9 books. Each book’s author is traditionally attributed to the titular prophet.

The Former Prophets are narrative style texts covering the conquest of Canaan, the period of the Judges and period of Kings (United Kingdom followed by the successor two states).

- Joshua

- Judges

- Ruth

- Samuel (two books)

- Kings (two books)

- Chronicles (two books)

- Ezra

- Nehemiah

- Esther

From this list, Ruth and Esther are technically part of the third and final main grouping of Old Testament books, but are listed here because of the reordering that the main Christian bible follows today. The prophet Ezra is believed to have been the author behind both his book as well as the preceding Chronicles, and unlike all the books to date, Ezra was penned in Aramaic instead of Hebrew.

The historical and consistent narrative of the first six books has led scholars to believe the finalised form we have today was the result of efforts made during the Babylonian Exile of the 6th century BC. Ezra and Nehemiah are believed to have been finalised separately and much later in the 3rd century BC.

Ketuvim (Writings): 5 Books

The next five books contain the three Poetic books and form the central core of the Old Testament, all being written originally in Hebrew and all around the time period of the United Kingdom of Israel.

- Job

- Psalms

- Proverbs

- Ecclesiastes

- Song of Solomon

Nevi’im (Latter Major Prophets): 5 Books

The next grouping (sub-grouping in some structural analyses of the Old Testament) are the five major prophets. Majority of these writings were also in Hebrew although the later period saw Aramaic language also used for Jeremiah and Daniel. This period focused on the divided Kingdoms and the period of Exile in Babylon.

- Isaiah

- Jeremiah

- Lamentations

- Ezekiel

- Daniel

Nevi’im (Latter Minor Prophets): 12 Books

The final grouping of prophetic writings were written over a span of 200 years (8th to 6th century BC) with the exception of Jonah being written closer to the 3rd or 4th centuries BC.

- Hosea

- Joel

- Amos

- Obadiah

- Jonah

- Micah

- Nahum

- Habakkuk

- Zephaniah

- Haggai

- Zechariah

- Malachi

New Testament (27 books)

The formation of the New Testament can be grouped as follows:

The Gospels: 4 Books

Matthew, Mark, Luke and John are simply four versions attributed to each of the titular authors, presenting a slightly different focus on the Good News (literally that’s what “Gospel” means). They were accounts of the life of Jesus and his ministry, culminating in his death on the cross and subsequent resurrection three days later. It is believed by biblical scholars that the Gospel of Mark was the first to be recorded, followed shortly by Matthew and Luke. John was the final gospel to be recorded, in part due to the Apostle John living longer than his contemporaries.

Acts of the Apostles

Acts is understood to be a written historical narrative that follows Luke, such that some scholars group the two together. Combined with the four Gospels, these five books offer a historical narrative of the one single period spanning 4 BC through to the mid 30s AD.

Pauline Epistles

10 epistles are attributed to the work of Paul. As divinely inspired and holy letters, written by the apostles and disciples of Christ, to either local congregations with specific needs, or to New Covenant Christians in general, the following letters were written:

- Romans (Church of Rome)

- Corinthians (Church of Corinth x 2)

- Galatians (Church of Galatia)

- Ephesians (Church of Ephesus)

- Philippians (Church of Philippi)

- Colossians (Church of Colossi)

- Thessalonians (Church of Thessalonica x 2)

- Philemon (Church of Colossi – Philemon was a leader there)

Pastoral Epistles

Three additional letters are generally attributed to Paul and were written to an individual audience, where the recipient held leadership and pastoral responsibilities.

- Timothy (x2)

- Titus

Hebrews

Hebrews is uniquely set apart because it was written for a Messianic Jewish audience and the Pauline authorship has been debated over the years.

General Epistles

Seven final letters penned by other authors form the remainder of the New Testament bar one (Revelation).

- James

- Peter (x2)

- John (x3)

- Jude

Revelation

This final book was a prophetic and apocalyptic writing attributed to John. Like the Gospel of John, it is believed to have been written as one of the last texts accepted as being the legitimate New Testament apocrypha. This apocrypha was simply the accepted and authoritative collection of writings that we now accept as the New Testament.

Canonisation

The canonisation effort began around the turn of the first century AD, since extra biblical writings were also quite prevalent. Whilst the process was quite complex, the main debate was on the fringe texts; the 27 books that we now call the New Testament were 90% accepted as authoritative. Lists of the accepted books emerged during the 4th century which helped to finalise the discussion.

Early Translations

By the 2nd century BC, both Nevi’im and Ketuvim were accepted as authoritative texts, although not quite at the same level of reverence as the Torah. These formed the Jewish religious text. The conquest campaigns of Alexander the Great resulted in a growing influence of Greek in the Middle East and thus, the Septuagint (Latin for 70) became the first Greek translation of the Old Testament. The Septuagint remains the Old Testament canon for the Eastern Orthodoxy church through to today.

The New Testament was primarily written in Greek, with some of the Gospels written in the local Aramaic script. Combined with the Septuagint, the first complete bible “translation” would have been achieved in Greek.

With the spread and influence of the Roman Empire, Latin translations began to emerge for the whole New Testament by the 4th century, although parts and individual Epistles may have started to emerge earlier.

A Syriac version/translation also emerged around the same period; the language being native to the area around modern-day Syria.

Middle Age Translations

A handful of translations beyond the core Latin and Greek are traceable to the Middle Ages. However, Old English versions and other varieties are generally rare since translation was discouraged. Old French, Middle English and High German are just some of the few examples that survived to allow us a modern-day awareness of such translations.

Modern Translations

Whilst the Latin translation of the Bible became the official version of the Catholic church for a good 1000 years, the birth of Protestantism thanks to Martin Luther saw translations emerge in the local language around Europe:

- Lutheran Bible (German) – 1522

- Dutch – 1526

- Brest Bible (Polish) – 1563

- Tyndale Bible (English) – 1526

- Authorized King James (English) – 1611

With the Gutenberg printing press developed in the 16th century, the Protestant effort to translate the Bible was given a real boost. Since the 1900s, the use of dynamic equivalence versus formal (literal) equivalence has led to the emergence of even greater numbers of translations just within the English language. Using various forms and level of the two techniques for translations, a number of popular varieties of Bible translations are available today that help us perform a literary contextualisation of the Bible.

Formal Equivalence Translations

- American Standard Bible (ASB, 1901)

- Revised Standard Version (RSV, 1952)

- New King James Version (NKJV, 1982)

- New Revised Standard Version (NRSV, 1989)

- New American Standard Bible (NASB, 1995)

Moderate Dynamic Equivalence Translations

- New International Version (NIV, 1978)

- Today’s New International Version (TNIV, 2002)

Extensive Dynamic Equivalence Translations

- Good News Bible (GNB, 1976)

- New Living Translation (NLT, 1996)

- The Message (MSG, 2002)

It should be noted that all my memory verses were provided originally as GNB translations; the GNB was particularly favoured because the paraphrasing and use of dynamic equivalence made that bible edition conducive for children learning the Bible.

You must be logged in to post a comment.